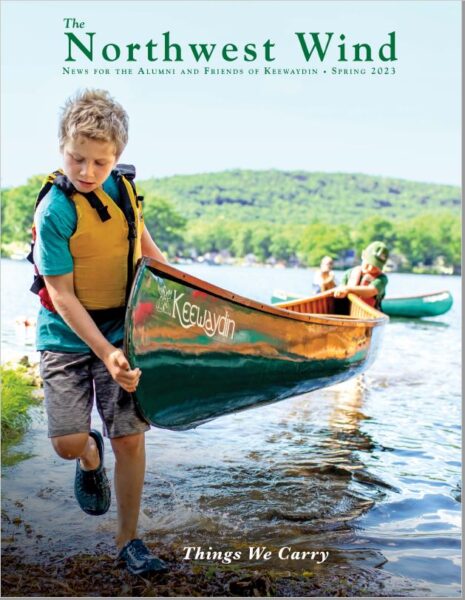

The Inconvenience of a Wood Canvas Canoe

The Inconvenience of a Wood Canvas Canoe by Ben Jacoff ’96 Wood canvas canoes are not convenient. Drag one across a small stone and that sacred green paint and fabric will offer little resistance to the stone’s sharp edges. There is no forgiveness in their planks, no second chance in a cracked rib. Paddle a wood canvas […]

The Relationship Between Nature, Humans and Keewaydin

From the Director: Bruce Ingersoll ‘76 At the prompting of his daughter Amelia ’09, Keewaydin Temagami’s Director was pressed to reflect on the relationship between nature and humans and Keewaydin. My daughter Amelia is a senior this year so I am enjoying the final days of being able to peer over her shoulder as she […]

Ooohing and Ahhhing My Way Down the Winisk

Ooohing and Ahhhing My Way Down the Winisk River By: Joe McClean I first heard about Keewaydin in 2010 when my wife and I were looking for a summer camp for our eldest daughter. Fast forward to the beginning of this year, my wife and three daughters had accumulated 16 years of Keewaydin canoe trips […]

Section A and A New “Bay”

Section A and A New “Bay” In 2016, John Frazier and Sam Morris teamed up to lead Section A to Ungava Bay, via the Leaf River. John and Sam also teamed up to write about the trip. Part 1, by John Frazier This year Section A paddled to Ungava Bay. While the destination was new […]

Better Than An Internship

Better Than An Internship: Takeaways From Being A Songa Staff By: Jenn Hare, ‘99 In recent years, the pressure on college students to take on summer internships towards a specific career has become stronger and stronger. The prevailing wisdom is that padding a resume and getting one’s foot in an industry door are essential to career […]

Testimonials From the Kids

From Keewaydin Kids Kids say the darnedest things. But they also have the most soulful insights into what makes each of Keewaydin’s camps great. Trying to persuade someone on the fence about a summer at Keewaydin? Looking to remember your own camping days? Look no further, because these kids have hit the nail on the […]

Abby Fenn Memorial Service

A service celebrating the life of Abby Fenn will be held on Sunday, August 30, beginning at 11:00am at the Keewaydin campus on Lake Dunmore, Vermont. A buffet lunch will follow. For more information or to RSVP Contact: Theresa MacCallum, theresa@keewaydin.org, 802-352-4247

Passing of Abby Fenn ’39

Dear Keewaydineesi, It is with great sadness that I bring you the news of the passing of Abby Fenn. He died early this morning while asleep at his apartment at Eastview in Middlebury. He was 93 years old. A memorial service will be held for Abby on Sunday, August 30 at 11:00am at Keewaydin Dunmore. A […]

Happy Holidays From Your Friends At Keewaydin

Happy Holidays! We hope these videos bring back warm memories of camping seasons past!

BREAKING NEWS! CHARITABLE IRA ROLLOVER Extended

CHARITABLE IRA ROLLOVER extended for those 70 ½+ — BUT ONLY THROUGH DEC. 31, 2014! The Charitable IRA Rollover was signed into law last week. Donors age 70 ½ and older may now transfer up to $100,000 from their IRA to a qualified public charity. This provision is in effect only through December 31, 2014, […]